By Jeremy Morrison and Sydney Robinson

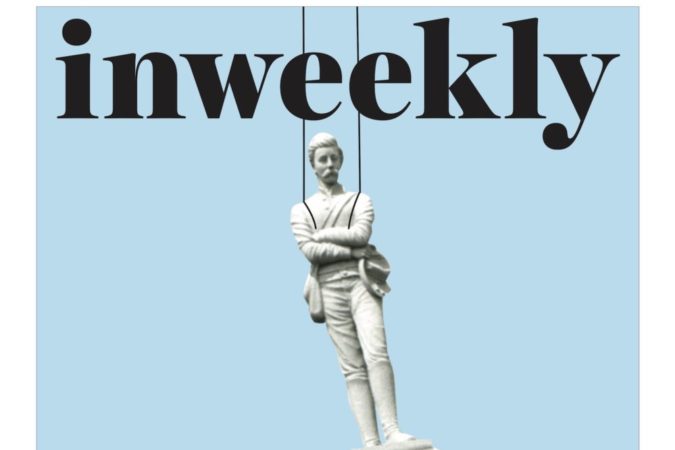

After more than a century, Pensacola’s Confederate monument is coming down. In a five-hour marathon of a meeting Tuesday night, the Pensacola City Council voted to remove the Lee Square Confederate monument and rename the square. At approximately 10:38 p.m., the vote came in 6-1, with only Councilman Andy Terhaar voting against the removal.

“At some point we must stop fighting the Civil War and embrace the humanity of all mankind,†said council President Jewel Cannada-Wynn, with a nod towards the “wonderful experiment of democracy†and “a history that should be behind us.â€

She spoke of the racism she has faced as a Black Pensacola resident, including being called the N-word multiple times, once by a young child.

“The monument is about racism,†she said. “I don’t see it as a Civil War reminder. I see it as perpetuating racism in our country.â€

The Confederate monument has overlooked downtown Pensacola from its lofty perch on Palafox Street since 1891. Dedicated to ‘the uncrowned heroes of the Southern Confederacy’ and ‘Our Confederate Dead,’ it features a South-facing soldier atop an obelisk, as well as tributes to Jefferson Davis, the president of the Confederate states, and local Confederate notables Edward Perry and Stephen Mallory.

The council also voted unanimously on the motion to restore the square’s name from Lee Square to Florida Square, its original name and a name it held as recently as 1906.

History vs. History

The council’s monument vote came after significant support for its removal, including from Mayor Grover Robinson, city staff, Pensacola News Journal, Inweekly, Greater Pensacola Chamber and Pensacola Young Professionals. A petition for removal on change.org received over 22,000 signatures.

Proponents of removing the monument contended that it celebrated a racist past, namely the Confederate mission to defend the institution of slavery and also later the Jim Crow-era effort to reinforce that racial divide. Those arguing to keep the monument defended it as a memorial to fallen soldiers and as part of the city’s history.

“As a white person, I feel ashamed walking by the Confederate statue downtown, and I can’t imagine how Black people feel,†said Christine York.

“It doesn’t glorify the Civil War, slavery or racism,†countered Mike Bates. “It is simply history.â€

The volleying public input presented a gaping divide on the subject. While one side described the monument as a “celebration of a racist past,†the other pleaded for city council to “not let these Marxists take over our country and take our statues down.â€

Those wishing to leave the monument alone accused officials of giving in to “kids pitching a fit in the candy isle†and described modern day activists, such as the Black Lives Matter movement, as Marxists, agitators, terrorists and “just a small, loud, radical bunch.†They implored council to delay any decision and to put the issue on a public ballot.

Proponents of removal argued that the monument reinforced an environment of pervasive racism and recounted a history of injustice. They described the monument as “more than offensive†and a “symbol of a shameful period of American history†and a relic best left in “the dustbin of history.†They quoted Desmond Tutu, as well as, surreally, Confederate General Robert E. Lee: “I think it wiser not to keep open the sores of war …â€

Both factions, perhaps inevitably, cited Nazi Germany in their rhetoric. While one side drew parallels between the Nazis and the Confederacy, the other viewed cleansing the city of the monument as akin to the sweep of Nazi propaganda.

Those arguing both for and against the removal of the monument also rested their rationale on economic grounds, contending that removing the monument would negatively impact historic tourism or, conversely, keeping the monument would tag the city as a racist locale folks would rather not visit.

Downtown property owner Debrah Dunlap told council that they should let the monument stand, thus casting the city in the “cultural tourism limelight.†State legislator Rep. Mike Hill argued that removing the monument would be a violation of the law, a position the city’s legal department rejected.

Ron Helms, who is seeking the District 5 city council seat, pushed for the monument’s removal, saying “it is time for Pensacola to heal.†Teniade Broughton, running for that same seat, urged council to “correct a historical wrong.â€

Pensacola Mayor Grover Robinson described the debate as “very passionate†and “very divisive.â€

“I think it shows a lot fo the challenges before you,†he told city council members. “The only way we’re going to get through this is by dealing with this respectfully.â€

‘Time to Let Go’

In her comments before the vote, Councilwoman Sheri Myers responded to multiple comments calling for the vote to be delayed for one reason or another.

“We have been discussing this since 2017,” she said. “We had many people come down to the City Council to speak in public and we received hundreds of emails and letters. I think that there’s been plenty of discussion.â€

Myers reflected on her hopes that the removal of the confederate monument “will not just be a symbolic gesture but the beginning of real change for our city.â€

Councilman Jared Moore urged the council and the public to consider that the debate which had been so passionate was “in a lot of ways preempted by the national narrative.†He joked that it was not a debate between “racist bigots on one side and Communist usurpers†on the other. He understood that the monument meant many things to many people, but for those who the monument causes pain, “it wouldn’t be fair to ask them to see it as a neutral, fond southern thing.â€

Councilman John Jerralds said he supported the monument being relocated, not removed.

“Instead of removal, I prefer the term ‘relocation’–that’s what the mayor is talking about,” he said. “Because history is what it is; it cannot be erased.â€

Councilman P.C. Wu echoed comments from Councilman Jerralds: “I want assurance from the mayor and his staff that it will be relocated either [to St. John’s] or the Historic Trust or somewhere equivalent because this means so much to so many people.â€

Councilman Terhaar explained that while he believed the Civil War was fought over the institution of slavery, he supported altering rather than removing the monument.

“I think we have an opportunity to do something where you can have community support for a monument that encompasses the diversity we have in the city,” he said. “I’m not going to support removing this at this time.â€

The council’s vote requires the removal of the monument but does not specify where the monument will go or provide a deadline for action. Still, the Council urged the Mayor and city staff to take swift action.

The mayor said that all options are on the table but that there are two receiving the most consideration: St. John’s and the UWF Historic Trust.

“St John’s [Cemetery] has indicated that they are willing to accept the statue, the other [option] is the Historic Trust,” said Mayor Robinson. “There’s been much discussion about how it can be presented in an educational light. We will evaluate everything but certainly those two come to mind.â€

The city plans to hire a contractor who specializes in historic statues to handle the safe removal of the monument as well as helping to plan how to safely relocate it.

Whatever happens to the monument it will be, logistically speaking, a heavy lift. Derrik Owens, the city’s director of public works and facilities, noted that the monument weighs about 12 tons, will have to be moved carefully, and will likely require the creation of a base on which to place it.

“Wherever it goes, it’s going to be involved to move the statue,†he said.

The task of removing the monument, Owens estimated, will likely take between 60 and 90 days. The plaques at its base could be covered up much sooner.

Regarding the proposal to place the monument in St. John’s, Councilwoman Ann Hill said that residents in the area around St. Michael’s Cemetery expressed concern about having to see the 42-foot monument from outside of the cemetery.

“People don’t want to have to see it from their porch,”said Hill. “My hope is that if we do relocate it, maybe not put it up 42 feet in the air.â€

Rather than relocating the full statue to either of the suggested locations, she suggested that the plaques could be placed at key gravesites in both St. John’s Cemetery and St. Michaels Cemetery.

“If this can be taken apart successfully, I don’t mind giving it to other people,” said Hill. “I don’t think it has to stay together.â€

The mayor and council both emphasized respectfully handling of the monument through whatever steps are taken.

“When [the monument] was defaced, we got out there immediately and cleaned it up,” said Mayor Robinson. “It’s still an asset of the city which we will respect as we work toward its relocation.â€