In October 2007, Sheriff Ron McNesby refused say to Escambia County had a gang problem. We quibbled over whether the local groups – Ast.-N-Jackson, Haynes Street Gang, the Montclair Boyz, the Shanty Town Posse and Warrington Village – qualified as gangs.

To learn about gangs on our public school campuses, we interviewed Steve Sharp, who headed the school district’s public safety, about what he was seeing in the schools for our cover story, “War on Gangs.”

- The same week we published the story, the Department of Juvenile Justice for Circuit 1, which includes Escambia, Santa Rosa, Okaloosa and Walton Counties, established a gang task force to help in prevention and intervention efforts – it was part of a statewide effort to develop a database to identify and share information on gangs and gang members.

Sam Burgess, the Circuit 1 gang liaison for DJJ, told Inweekly that law enforcement officials had noticed increased violence and other activity by juveniles both locally and across the state.

“We do see a lot more violent crimes by juveniles,” said Burgess, a 27-year veteran of the department. “We don’t know if it’s all gang-related, but our belief is it could be.”

He added, “We recognize there is a gang problem and by identifying gang members and developing intervention and suppression programs with the schools we hope we can combat the problems. Our gang issues are not currently at the level of a Miami or Orlando or other larger circuits and we want to keep it that way.”

‘I’m Coming For You’

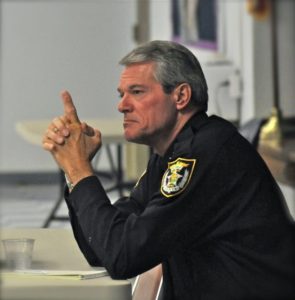

In May 2009, newly-elected Sheriff David Morgan announced a war on gangs. He declared that the “explosion” in gang violence would not be tolerated – “I’m coming for you. The days of frolicking in my county are over.”

In May 2009, newly-elected Sheriff David Morgan announced a war on gangs. He declared that the “explosion” in gang violence would not be tolerated – “I’m coming for you. The days of frolicking in my county are over.”

At the press conference, Sgt. Rick Vinson, who ran the ECSO gang task force, gave a presentation on the history of gangs in the county since the mid-90s and stressed the rising problem on a national level. “The FBI has reported that 80 percent of crimes nationally are committed (by gangs). We’re not far off from that here.”

Besides ECSO investigators, the gang unit included one supervisor and a crime analyst from the FDLE. Sheriff Morgan estimated that the county had roughly 11-15 known gangs.

From October 2007

The War On Gangs

by Duwayne Escobedo

For the first two weeks of school, one gang member attended class at Washington High School by acquiring another student’s schedule. In the confusion of the first few days of the new school year, especially over enrollment, the teenage boy could flash the schedule to teachers and get away with sitting in the classroom.

For the first two weeks of school, one gang member attended class at Washington High School by acquiring another student’s schedule. In the confusion of the first few days of the new school year, especially over enrollment, the teenage boy could flash the schedule to teachers and get away with sitting in the classroom.

He was going to class. He wasn’t causing any problems.

But then, the gang member got caught standing in the school’s hallway between classes. He was sent to the dean’s office.

There, a phone call to the Department of Juvenile Justice revealed an order for him to be picked up and brought in. A search of his backpack revealed a shiny, chrome-plated 9 mm pistol.

Thankfully, there was no school shooting but there had been rumors of a shiny gun being shown off.

Steve Sharp says the incident confirmed to him that the Escambia County School District has a growing gang problem. It also confirmed that the school district’s stepped-up efforts this year to prevent and suppress gang-related activities at schools are on target.

Sharp, who heads public safety at the district’s schools, reports witnessing more gang issues during the past three years, a trend in school districts across Florida.

“We needed to do this before it gets out of hand and someone does get hurt,” says Sharp, the Escambia County School District Protection Services Division Chief for more than five years. “We decided we needed to focus on it and get it under control. We wanted to be proactive. We don’t want something to end up on our doorsteps.”

GANGS ON THE RISE

And information from gang experts is that they expect gang activity to increase in the next two years, with gangs moving from cities into less populated areas as they try to expand lucrative illegal activities, such as the sale of marijuana and methamphetamines, and move into areas where law enforcement may not be familiar with them, so they can operate under the radar.

In Florida, gangs in the central part of the state, for instance, are affiliating more with gangs in North and West Florida to spread their drug trade.

The National Alliance of Gang Investigators Association reports in its latest assessment of gangs: “As gang migration occurs at increasing levels across the country, new and emergent trends in criminal activity will surface. New communities will feel the impact of gangs in their neighborhoods and will see the slow erosion of safe havens for their children. Gangs will move into jurisdictions where law enforcement may have less knowledge of their activities and culture and may not have the support to combat them.”

Pensacola law enforcement agencies report noticing the migration, for example, with one member of a national gang based in Los Angeles posing in a photo on the Internet with a local gang.

Sean Dockery, a Pensacola Police Department school resource officer at Pensacola High School the past four years, says an influx of national gangs, like the Crips, Bloods, Folk Nation or Sur 13 hasn’t happened–yet.

“There’s no big national gangs here,” the local gang expert says. “They’re more regional or affiliated with housing projects, like Attucks Court. There are some national elements testing the waters. We’re staying on top of who is doing what. We want to stop it before it gets here full force.”

WHO’S WHO

Some names of the local gangs include the Ast.-N-Jackson, Haynes Street Gang, the Montclair Boyz, the Shanty Town Posse, Warrington Village and others. Law agencies say they’re not sure how many gangs and how many people are involved.

But you can find some of them on MySpace or other websites posing for “money shots,” which usually includes a gang member holding drugs, wads of cash or guns. The profane sites talk about sex, money, drugs and parties with members going by names like “Durrti Muthafuckin Mike,” claiming incomes higher than $250,000 and proclaiming, “Imma ghetto superstar.”

Violence has not risen to the level, say like that seen in a Palm Beach County, where gangs are responsible for 10 shooting deaths in the past 15 months. But drive-bys have been reported, including one 15-year-old shooting 12 to 15 rounds from a .380-caliber semi-automatic at a Saufley Pines Road home in August and another unidentified black youth firing a black semi-automatic handgun Oct. 7 from a Mustang at seven onlookers at a Sandalwood Drive residence.

“They’re much more intense than they used to be,” Sharp says. “It’s not like hundreds are running around in our schools. But the sophistication and intensity is increasing.”

Some of the measures taken by the school district are putting extra deputies on duties for events, for instance, the opening day of school; stepping up the presence of police officers at football, basketball and other games and using Escambia County Sheriff’s Office helicopters; enforcing a dress code at school and school events that mandates no gang attire, no baggy pants or shirts and shirts tucked into pants with a belt; and training teachers and school administrators on how to recognize and deal with gangs.

The school district is developing or considering developing additional efforts, such as setting up a task force of local, state and federal law agencies and community and church groups to improve communication and awareness about gangs. It also may add to the dress code a prohibition against T-shirts with words on them, which gang members sometimes use to identify themselves. In addition, a database is being established with information about Pensacola area gangs that will tie in with a statewide database in an effort to combat potential problems.

Pensacola High School Principal Sara Lewis says this school year’s training for faculty and staff was particularly enlightening.

“It made us all aware of things we haven’t thought about,” she says. “We want to help make sure (gang-related activity) doesn’t filter into our schools.”

This year, a major focus has been on ensuring safety at high school athletic events. Helicopters have been deployed, gang attire is not allowed and people are required to sit in their seats. If groups of teenagers are milling around, they’re broken up and asked to sit down.

GANG AWARENESS

Sharp says he recalls kids standing 10 to 12 people deep along the track at some high school football games in the past. No more.

No fights or major disturbances have been reported at any football games this season.

“We can’t allow that,” Sharp says. “Football and basketball games are where we have issues. That’s where we have crowds. We’re not having problems at baseball, soccer or softball games. We’ve even used the sheriff’s helicopters a lot. It is a great tool. We’ll put them up at the end of a game and they’ll circle the campus and neighborhoods where we have problems. It makes a difference.”

Dockery says the steps being taken by the school district are helping thwart gang-related activity at the schools.

“The school district is doing a great job of trying to keep it out of the schools,” he says. “I have seen a lot (of gang members) representing themselves as being into drugs and into weapons. But I have certainly not seen anything like that at the school.”

Palm Beach County School District Police Chief Jim Kelley says acknowledging a problem and then cooperation and communication between various law enforcement agencies are keys. His agency recently received $450,000 in federal funding to improve communication technology between the police and schools and to train additional gang intelligence detectives.

“We are happy and grateful that Congressman (Tim) Mahoney got funding to allow us to be among the first in the nation to be able to share real time gang intelligence with our local police officers and deputies,” Kelley says. “Knowledge is power. Through knowledge we can be more proactive and ensure the safety of ourselves and the community.”

Dockery says already the increased awareness of gangs among school faculty and staff and local law enforcement agencies is helping to eliminate problems.

For instance, school officials noticed STP hats and garb being worn by kids who did not appear to be your typical NASCAR fans. Turns out the Shanty Town Posse gang adopted the symbol as their own. STP hats and clothing were banned by the school district.

Warrington Village gang members flash the numbers three and four with their fingers. The address of the housing project is 34 Patton Drive. Others roll up a pant leg, pull a pocket inside out or fly their gang colors from a handkerchief sticking out of their pocket.

“We’re in the awareness and intelligence gathering stages,” Dockery says. “This is not a new problem. What we have are new tools to identify it and new tools that give us insight into what’s going on.”

THE RESULTS

While he recognizes a problem exists, Dockery emphasizes the number of gang members and gang activity is still low in the school setting.

In fact, the Department of Juvenile Justice reports school referrals accounted for 18 percent of all of its referrals in Escambia County and translated into a rate of 26 students per 1,000 in student population in the school district. In Santa Rosa County, school referrals were 14 percent of all DJJ referrals and the county had a rate of 8 students per 1,000 students being referred.

Statewide the DJJ reports school referrals account for 17 percent of its cases and 17 students per 1,000 in student population. Of course, not all of those referrals involve gang-related activity.

Meanwhile, 24 percent of the referrals are for drug and weapon offenses, 40 percent are for disorderly conduct or misdemeanor assault and battery and 64 percent of all offenses are misdemeanors in Florida, a Juvenile Justice report reveals.

“I don’t want to give parents the impression and have them worrying that there are gangs all over our high schools and they’re killing each other,” he says. “They’re not. I would have no problem sending my children to any high school in this county. Usually, we’re dealing with five or six people during the day who are causing a majority of the problems out of a population of about 1,500 students.”

On a recent weekend, Sharp learned of fighting and some shots being fired between the rival Haynes Street and Montclair Boyz gangs. He immediately requested more police presence at certain schools when they opened and closed. No problems occurred.

“So far, we’ve been very effective,” he says. “It’s already had a big impact. We’ve had a few complaints. But most parents are coming up to us and saying they appreciate what we’re doing.”