We all know those Keystone Cops. Escambia had its own version. They were Escambia code enforcement officers.

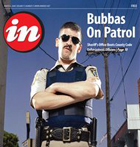

Bubbas On Patrol

By Duwayne Escobedo, published 3/5/08

Sheriff’s Office Boots County Code Enforcement Officers

We all know those Keystone Cops. Ever since the silent film series of the totally incompetent policemen first appeared in 1912, Hollywood has given us the hilarious Barney Fife in “The Andy Griffith Show,””Police Academy,””Reno 911!,”etc.

Well, let us introduce you to a few real Keystone Cops-Charlie Walker, Sotirios Thagouras and Steve Littlejohn.

They are Escambia County code enforcement officers who currently have civil suits pending against them in the U.S. District Court’s Northern District of Florida in Pensacola. The federal suits allege wrongful conduct that violated Escambia County business owners’ and citizens’ constitutional rights in two different cases.

Escambia County Sheriff Harry “Ron”McNesby is also named in the lawsuits for deputizing the county’s code enforcers.

We like to refer to these episodes as “Bubba’s on Patrol.”

Sounds pretty funny, don’t it? Our sense of humor won’t let us NOT make fun of it. Ain’t so humorous, though, when you’re the one who’s being jacked around by Bubba.

THE BUBBA CASES

Let’s consider Case 1 involving Carl and Sharon Gilbert, shall we?

The facts of the case alleged in the suit filed in federal court last month are that Carl Gilbert relocated his business, Southland Site Contractors, to Longleaf Drive in March 2005. Gilbert, who has owned his own business since 1999, had his previous office damaged by Hurricane Ivan.

He got an occupational license from Escambia County for construction and debris work and opened for business in October 2005. Under County Ordinance 82-131, businesses aren’t required to get solid waste permits, if they don’t haul residential garbage.

About two months later on Dec. 15, 2005, Thagouras visited Gilbert and told him that he was investigating possible zoning and licensing violations. Five days later, Thagouras issues a cease and desist order, claiming a zoning violation and claiming that Gilbert needed a solid waste permit.

The Gilberts, who have more than 20 trucks and about a dozen employees, apply for a solid waste permit, even though, they aren’t required to do so. They are given permission by the Escambia County Department of Solid Waste to operate while the permit is being processed, which takes about three month to obtain.

But when Southland Site Contractors goes to dump construction debris at the Saufley Landfill on Jan. 5, 2006, they are refused by John Englund. The suit alleges that’s because Thagouras “threatened to cause problems”for the landfill and Englund. He also allegedly tells the landfill operators that Gilbert was operating illegally and without insurance.

That same day, Gilbert contacts Thagouras to explain that nothing prevents him from operating. Thagouras then says he wants to shutdown every jobsite Southland is working and wants to see the company “shut down,”the federal suit says.

The next day on Jan. 6, 2006, the Gilberts ask Escambia County Commissioner Mike Whitehead for help. Whitehead checks with the county attorney and tells the Gilberts that Thagouras lacks authority to prevent their company from dumping construction debris at the private landfill.

But on Jan. 7, 2006, the Saufley Landfill turns away Southland trucks again. And the suit alleges, the refusal costs Southland a demolition contract.

Two days later, Saufley Field’s Englund calls Gilbert to tell him that Thagouras has given his permission for six loads to be dumped. Thagouras requests to meet with Gilbert and discuss the issue. Gilbert informs Thagouras that he is at the office every morning between 7:30 and 8 with two of his three children because they walk across the street to school with their friends.

BUBBAS USE HANDCUFFS

On Jan. 10, 2006, Thagouras shows up at the Southland office with an Escambia County sheriff’s deputy and several other code enforcement officers and arrests Gilbert in front of his children, the civil lawsuit claims.

Gilbert is arrested for allegedly committing two violations of obstruction of right of way, one violation of the franchise haulers agreement, one zoning violation and one setback violation.

Furthermore, Thagouras, with the approval of Walker, the county’s code enforcement supervisor, gets a second warrant for Gilbert’s arrest on Feb. 10 alleging the same violations. Gilbert is arrested again on Feb. 28, 2006.

The suit filed by the Gilberts’ attorneys James Murray and Eric Stevenson says “the arrest was unnecessary and further that Thagouras was attempting to harass and humiliate [Gilbert] with the second unlawful arrest.”

In a March 8, 2006 meeting attended by Walker, Thagouras’s boss, an Escambia County attorney, Escambia County Planning & Zoning official, the Gilberts and their two attorneys, Walker admits there is no setback violation, no zoning violation and that Southland did have a pending solid waste permit with the county.

However, after the meeting, Walker and Thagouras failed to notify the State Attorney’s Office to drop those charges in violation of the due process rights guaranteed by the Fifth and 14th Amendments of the U.S. Constitution.

On June 6, 2006, Southland’s solid waste permit is approved.

On June 8, 2006, Gilbert is found not guilty of all charges by Escambia County Judge Thomas Johnson.

SAGA CONTINUES

But the story doesn’t end here.

On June 9, 2006, Thagouras applies for a third arrest warrant for Gilbert on the same violations as before, violations a judge found him not guilty of a day before.

The suit says that Thagouras requested the Santa Rosa County Sheriff’s Office execute the warrant and informed them that Gilbert was dangerous. A Santa Rosa County SWAT team arrests Gilbert for the third time July 24, 2006, at his Santa Rosa County home in front of his three children, now ages 19, 13 and 12, and neighbors.

This time, the State Attorney dismisses the case, citing the fact that Gilbert had already been found not guilty on the same charges.

The Gilberts and their attorneys declined to speak to the Independent News about the case pending before U.S. District Court Judge Casey Rodgers.

But Stevenson does admit, “This has been difficult on him and his family and his business.”

Now let’s move on to Case 2, which is similar to Case 1. It also involves Saufley Landfill, construction debris haulers and county code enforcement officers Walker and Thagouras.

In this case, Murray and Stevenson are representing Robert K. Mandel and Sharon Mandel. Sharon Mandel owns A Prestige Services, also known as R-C Express.

The company rents containers for non-household debris collection in Escambia County.

In February 2006, R-C Express gets its occupational license, but it is informed by Walker that they also need a solid waste permit. However, the Tax Collector’s Office rules that the only permit required is the occupational license. The Mandels get an application for a solid waste permit to be on the safe side and dump debris at the private Saufley Landfill, which is in competition with the Escambia County-owned landfill.

CASE DISMISSED

Thagouras obtains an arrest warrant on April 18, 2006, for Robert Mandel, even though, he is not an owner of the business. Three days later, Robert Mandel tells Thagouras and Littlejohn at the R-C Express office that he does not own the company and shows them a completed solid waste permit application.

Nonetheless, the Escambia County Sheriff’s Office on May 2, 2006, arrests him.

On Feb. 21, 2007, the State Attorney dismisses the case.

Walker, a 21-year code enforcement veteran, and Thagouras, who joined the division in June 2004, are remaining mum on the federal civil suits. Calls to them are referred to Escambia County Administrator Bob McLaughlin.

McLaughlin says, “It’s a very difficult job,”and adds, “They are innocent until proven guilty.”

The Escambia County Commission voted Feb. 17 to pay for the legal defense of the code enforcement officers after the Sheriff’s Office informed the county that they were not covered under its liability insurance.

Whitehead, the commission chairman, also declines to talk about the lawsuit. But, in general, he applauds the work done by the code enforcement officials to clean up areas of the county, such as Brownsville.

“They do a lot of good,”he says. “There may be some complaints but for the most part I think people are very happy. They’ve made an impact.”

Escambia County made a concerted effort to bolster its code enforcement department in the wake of Hurricane Ivan’s destruction.

Pre-Ivan the county employed 13 code enforcement officers and now has 23 on staff. Two years, ago the budget was $1.3 million. The current budget for code enforcement is $2.4 million. It’s funded by fines and fees ($1.6 million), the general fund ($300,000) and solid waste ($500,000).

SHERIFF PULLS POLICE POWERS

Sheriff McNesby also helped elevate the jobs when he agreed to deputize them. McNesby and the county code enforcement officers earned lots of praise and publicity for its much ballyhooed “Operation Brownsville” in early 2007-a 30-day push led by the Sheriff’s Office to clean up yards, to lock up drug dealers and prostitutes and to push homeless people to other parts of town.

But two days after the Escambia County Commission agreed to defend Walker, Thagouras and Littlejohn, McNesby yanked their commissions on Feb. 19.

McLaughlin admits, “It was a blow to their egos.”

In a Feb. 19 memo to Walker from McLaughlin, which was obtained by the Independent News through a public records request, McLaughlin informs the officers that McNesby “has withdrawn all affiliation with BCC Environmental Code Enforcement and has asked that all employees return their commission cards to the HR office of the Sheriff’s Office as soon as possible.”

McLaughlin’s memo notes:

Code enforcement officers or CEOs don’t have arrest powers under Florida law.

CEOs are not entitled to bear arms. However, they are authorized to “apply for and utilize valid concealed weapon permits for the purpose of self-defense.”

CEOs can’t carry a firearm in a holster displayed openly on his or her belt. It must be concealed.

CEOs can’t drive vehicles with blue lights. “We will have to change the lights to amber or remove them altogether.”

CEOs will be allowed to wear body armor as a component of their official uniform.

“It is very clear what they can and cannot do,”McLaughlin says recently.

UNDER MCNESBY’S CONTROL?

The civil suits by the Gilberts and Mandels also name McNesby as a defendant. It claims that McNesby had the responsibility to supervise and train code enforcement officers since he gave them authority as deputy sheriffs to arrest and to take into custody individuals who violate state laws and county ordinances.

The suit says the sheriff should have known that the “lack of adequate policies, procedures, training and supervision”would result in constitutional violations.

But Sheriff’s Office Attorney Darlene Dickey says the code enforcement officers were never McNesby’s responsibility.

“The sheriff was not their employer,”she argues. “He can’t tell them what they should or shouldn’t be doing.”

In fact, the county and Sheriff’s Office has gone back and forth since at least July 2, 2007, on what authority McNesby’s commission gave the code enforcement officers in records obtained by the Independent News through its public records request.

Dickey writes in a July 2, 2007, letter to Assistant County Attorney Ryan Ross that the sheriff allowed the use of “police powers in a limited capacity.”But that power was solely to enforce litter laws and code violations, she adds.

Dickey’s memo states: “As you are aware, the Code Enforcement Officers are granted limited authority by the board, and the sheriff does not intend to expand that authority. If a traffic stop is done, the sheriff expects written documentation in the form of either a warning citation or a Uniform Traffic Citation. The code enforcement officers should call a uniformed deputy to assist any time a separate criminal violation is discovered during the course of a traffic stop (i.e. DWLS, drug possession, outstanding warrants, etc.).”

But in e-mails between Dickey and Ross in late January 2008, the county asks for more clarification. “The county now requires that CEOs [code enforcement officers] be certified by the CJSTC [Florida Department of Law Enforcement’s Division of Criminal Justice Standards & Training Commission]. If a CEO is certified, does that make the CEO a law enforcement officer under Florida law? Or does the CEO need to be deputized or hired by a police department?”Ross asks Dickey.

In her Jan. 31, 2008, response, Dickey notes again that the sheriff does not employ the code enforcement officers and does not issue them weapons or handcuffs.

“The sheriff has never intended to make the CEOs deputies under his direction and control. The ordinances establish the positions and the authority of both Code Enforcement and Environmental Law Enforcement Officers in great detail, and the sheriff has always intended for the CEOs to act solely within those perimeters,”Dickey writes.

‘GARBAGE MEN WITH GUNS’

If you believe the Sheriff’s Office and county officials, the withdrawl of the code enforcement officers’ commissions is completely unrelated to the lawsuits. You be the judge.

“None of this stems from any of the complaints,”Dickey maintains in a recent interview with the Independent News. “This in no way was done because the sheriff is displeased with what they’ve done or thinks they’ve done anything wrong. That has played no factor whatsoever in the decision-making. The sheriff and McLaughlin have been meeting on this for months.”

Meanwhile, more citizens are stepping forward with complaints about county code enforcement officers as a result of the Gilberts’ and Mandels’ federal lawsuits.

Brownsville resident Ron Stewart says during “Operation Brownsville”in July 2007 that Sheriff’s Office helicopters flew over his house and he witnessed deputies with binoculars and cameras.

A day later, Stewart says a county code enforcement officer showed up at his door, demanded to take a look at his backyard, said she didn’t need a warrant, hopped his fence and stormed behind his house. Stewart says a crowd of other law enforcement officers waited in his front yard.

Stewart, who says his neighbors refer to code enforcement officers as “garbage men with guns,”says he isn’t exactly sure what the code enforcement officer expected to find. He speculates she thought he was growing marijuana plants but all he was growing was tomatoes. She never returned.

“I’m all for cleanup 100 percent,”he says. “But she walked into my yard with her hand on her gun. It was crazy. You can’t ever get them when you have a real complaint.”

Bubbas On Patrol Timeline

October 2005 Carl R. Gilbert II relocates his business, Southland Site Contractors, to Longleaf Drive. He gets an occupational license to haul construction debris and opens for business.

Dec. 15, 2005 Escambia Code Enforcement Officer Sotirios Thagouras visits Gilbert and tells him that he is investigating possible violations. Five days later, Thagouras issues a cease and desist order, claiming a zoning violation and lack of a solid waste permit.

Jan. 5, 2006 Gilbert’s Southland Site Contractors goes to dump construction debris at Saufley Landfill and they are allegedly refused because Thagouras told the landfill operators that Gilbert was operating illegally.

Jan. 6, 2006 Gilbert asks Escambia County Commission Mike Whitehead for help. Whitehead checks with the County Attorney and tells Gilbert that Thagouras lacks authority to prevent the dumping of debris at the private landfill.

Jan. 7, 2006 Southland trucks are turned away at Saufley Landfill again.

Jan. 9, 2006 Gilbert is told by Saufley Landfill operators that Thagouras has given permission for six loads to be dumped.

Jan. 10, 2006 Thagouras shows up at the offices of Southland with a deputy and several code enforcement officers and arrests Gilbert in front of his children. He’s charged for allegedly committing an obstruction of right of way, violation of franchise haulers agreement, zoning violation and setback violation.

February 2006 Sharon Mandel gets occupational license for her company R-C Express, which rents containers for non-household debris collection in Escambia County. Sharon and her husband, Robert K. Mandel, are informed by Escambia County Code Enforcement Supervisor Charlie Walker that they also need a solid waste permit.

Feb. 10, 2006 Thagouras gets a second warrant for Gilbert’s arrest alleging the same violations.

Feb. 28, 2006 Gilbert is arrested a second time.

March 8, 2006 Walker, Thagouras’s boss, allegedly admits that there is no setback violation, no zoning violation and that Southland did have a pending solid waste permit. However, Walker fails to notify the State Attorney to drop those charges against Gilbert.

April 18, 2006 Thagouras obtains arrest warrant for Robert Mandel, even though he is not the owner of R-C Express.

April 21, 2006 Thagouras asks Robert Mandel to meet him at the R-C Express offices. Thagouras and fellow code enforcement officer Steve Littlejohn issue him a notice of violation. Mandel gives them a completed application for the Solid Waste permit.

May 2, 2006 Robert Mandel is arrested for code enforcement violations.

June 6, 2006 Southland’s solid waste permit is approved, even though it doesn’t need it.

June 8, 2006 Gilbert is found not guilty of all charges by Escambia County Judge Thomas Johnson.

June 9, 2006 Thagouras applies for a third arrest warrant for Gilbert alleging the same violations as before.

July 24, 2006 Gilbert is arrested for a third time at his home in Santa Rosa County in front of his wife, Sharon, three children and neighbors. Thagouras allegedly informed the Santa Rosa County Sheriff’s Office that Gilbert was dangerous and the Santa Rosa County SWAT team shows up to arrest him.

Oct. 30, 2006 State Attorney dismisses the prosecution of the third arrest warrant because Gilbert was already found not guilty of the same charges.

Feb. 21, 2007 State Attorney dismisses the county code enforcement’s case against Robert Mandel.

July 2, 2007 The Escambia County Attorney’s Office and Sheriff’s Office begin going back and forth on what authority the sheriff’s commission gives the code enforcement officers. Sheriff’s Office Attorney Darlene Dickey writes in a July 2, 2007, letter to Assistant County Attorney Ryan Ross that the sheriff allowed them to use “police powers in a limited capacity.”

Dec. 31, 2007 Attorneys Eric Stevenson and James Murray file civil lawsuit against Escambia County code enforcement officers Charlie Walker, Sotirios Thagouras and Steve Littlejohn and Sheriff Harry “Ron” McNesby on behalf of the Gilberts and Mandels.

Jan. 31, 2008 The sheriff’s attorney, Dickey, responds to county questions again about the scope of code enforcement officers’ police powers. She notes that the sheriff does not employ the code enforcement officers and does not issue them weapons or handcuffs. She adds: “The sheriff has never intended to make the CEOs deputies under his direction and control.”

Feb. 12, 2008 The Gilberts’ case is assigned to U.S. District Court Judge Casey Rodgers, while the Mandels’ case is moved to U.S. District Court Judge Roger Vinson.

Feb. 17, 2008 The Escambia County Commission agrees to defend Walker, Thagouras and Littlejohn and pay for the legal defense of the code enforcement officers in federal court after the Sheriff’s Office informs the county that they are not covered under its liability insurance.

Feb. 19, 2008 Escambia County Administrator Bob McLaughlin sends a memo to Walker, the head of code enforcement, notifying him that the sheriff has withdrawn code enforcement officers’ commissions and outlines their new job duties.