On “Real News,” we often talk about Sena Maddison’s great-uncle, a WWII pilot killed on a bombing mission.

This article was first published in Inweekly on Nov. 11, 2010

By Sena Maddison

I have always had Bobby’s wings. I don’t remember when my father, Harry Maddison, gave me Bobby’s wings. I wore them a lot in the 1980s when it was stylish to wear paramilitary wear. I had boyfriends serving our country and was proud that Bobby had died for his country. Before I left for his funeral, I took them out and held them. My father gave the wings to me so I would understand Bobby’s sacrifice. It was for my father, and because of my father, I went to Bobby’s funeral.

On Sept. 18, 2010, the United States Army made right what went wrong in my family 66 years ago.

Bobby was the youngest son in my grandmother’s family. They were English. That is what is especially interesting about this story.

My great grandfather, William Bishop, left England for America first and worked as a cab driver to raise the money for his family to follow: my grandmother Irene, her sister Constance, and two younger brothers, Bernard and Bill.

Bobby was born in America. They eventually all became Americans, all of the children together, except for my grandmother. Nobody really knows why, whether it was just to be contrary or she honestly just wanted to be British, but the whole family would tease her every year when she had to go register as an alien – still, she never went to the trouble of becoming a citizen.

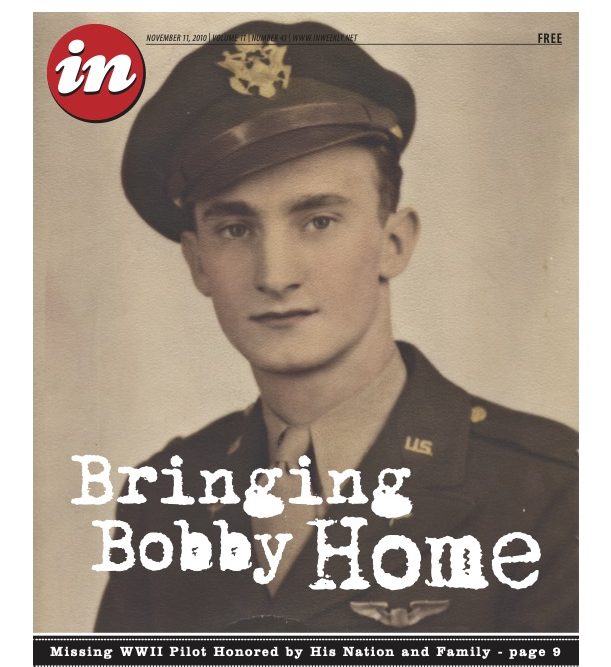

Robert “Bobby” Bishop, my father’s uncle, was born in 1920 in Illinois. Because he was so much younger and also because his mother had died and his father remarried, he spent a great deal of time with his sisters, sometimes living with my grandparents, my aunts Joyce and Sally, and my father in their small apartment in Chicago.

“We were poor, but we didn’t know it,” Aunt Joyce told me. “I remember when the rent went up to $30 a month, and that was tremendous. If we decorated the apartment ourselves, the rent was cheaper, so we did. And since Aunt Connie never married, she always had very stylish castoff clothes that would be cut up to make dresses for us.”

Connie was famously stylish. She had a penchant for a particular shade of light, almost turquoise blue that she often wore, and everyone referred to her as “Connie Blue.” It must be genetic. As I packed for the funeral, standing in front of my closet, I realized that most of my dresses are that same shade of blue.

Connie was especially close to Bobby and perhaps suffered the most when he disappeared.

RETURNING TO ENGLAND

Bobby had only been married for two months when he became a pilot. The family had, oddly enough for the time period, a color film camera. There are a great many grainy, color home movies of Bobby in uniform, with his wife Marilyn, and with Connie, my grandmother and the children, walking slowly toward the camera (because, with no sound, this is the most creative anyone ever was with a camera in 1941). There is also simulated footage of Bobby leaving, headed off to war in a big black car with everyone chasing behind it waving. My 10-year-old father and his sisters are in coats, still looking very English for all of their 25 years in America.

Bobby became an Army Second Lieutenant and pilot of a B-24 Liberator. I can’t help but find it fascinating that he ended up back in England. Wendling, Norfolk Station, was not 200 miles from Maidstone, the Kent town his family had left 25 years earlier. When I was a child, my family still spoke with subtle English accents; he might have felt very at home there.

While most of the crews had official pictures of themselves outside their planes, the one lasting photograph of Bobby’s crew was taken in an English pub. All in uniform, some drinking beer, some whiskey, they look happy. They were very young. Bobby was 23, and I imagine there were great big band tunes playing.

What is bothersome in this photo is Bobby. He has his arms crossed. And even then, he looks like an echo of man. He was responsible for all these happy boys. He is not smiling. It looks as if the weight of the whole European Alliance is on his thin, 23-year-old shoulders. He is balancing all in this photograph.

THE BISHOP PLANE

The other thing that is different about Bobby’s crew is that I have not been able to find a name given to that plane. In all official reports, the other planes were referred to by their nicknames – usually named after some pilot’s small-town sweetheart. Bobby’s plane is always only referred to as “The Bishop Plane,” and I wonder why he never named it.

Did the plane have a name? I know my family. It would have been bad luck not to name the aircraft. Unless you thought its existence was fleeting; unless your time on this Earth was so short and your responsibility so huge that a name was too powerful a thing to utter at that moment. I think in the weeks leading up to the assault, Bobby knew things we, almost 70 years later, can’t fathom.

It was huge. And it was only Bobby’s second mission as a pilot. On the night of April 29, 1944, over 600 B-17 flying fortresses and B-24 Liberators were sent to bomb the railroad system of downtown Berlin. The skies were black with our planes. “The Bishop Plane” never returned.

There was much confusion about this. Over Hannover, Germany, they encountered heavy German air fire, and one of the planes (called “Doodlebug,” another Liberator) saw a plane go down, but they didn’t think it was Bobby’s plane.

So Bobby was simply missing. The whole family, especially devastated Connie and the children, wanted to believe each night when they went to sleep, that Bobby was a prisoner of war, maybe in a terrible German concentration camp, but still out there somewhere, and that he would just walk back into that Chicago apartment one night, in his Army coat.

While in Rockford this past month, I thumbed through Aunt Connie’s scrapbook. She kept every Army change-of-address form she ever filled out when she moved to Rockford and when she changed apartments so that Bobby would be able to find her when he came home. Something in her didn’t want to give up hope.

I never had any illusions about this, however. I was always told, and I always understood, that Bobby’s plane had gone down in Germany, fully laden with bombs, and it had absolutely disintegrated. The crew was vaporized. There was nothing left. I understood from the start that Uncle Bobby had died for his country, and that was that.

There was nothing left.

ARMY MAKES IT RIGHT

That all changed in 2003. A German citizen, Enrico Schwartz, dug on the site in Meitze, Germany, where the plane had gone down and found remains, as he put it, “small enough to hold in two hands.” What he held in two hands was the 10-member crew of the Bishop plane. And the Army thought they could make this right. The Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command Central Identification Laboratory took the remains, and in 2005 sent a crew over to dig.

In 2008, my father got a phone call that struck us cold. They wanted his DNA. They thought they had found Bobby. Aunt Connie had died in 2004, the last of her generation and just four years too soon to see her beloved brother come home. So, it fell upon my father to give his DNA to identify Bobby. Dad gave his DNA, and we waited.

They found a piece of Bobby’s jaw, five teeth intact, a fragment of his tibia, a fragment of his femur, and, unbelievably, a fingernail. They identified him using my father’s DNA. They found enough of all 10 crew members, that through the DNA of their families, to bring them all home.

Bobby had something else, though. His dog tags were found, melted, bent in two, but you can still read his name upon them. Aunt Joyce said when Casualty Assistance Officer Lt. Col. Vince Barker put those in her hands, that is when it all came back and she broke down.

The family has gotten to know the Army’s Casualty Assistance Officers through the preparations for bringing Bobby home. Their dedication is profound.

FLYING BOBBY HOME

On Sept. 17, my father and I flew to Chicago for the funeral. We were picked up at the airport by Staff Sergeant Swington, or “Swing” to his friends.

Swing is from Chicago, young and energetic, only barely turning down the hip-hop on the stereo. He had much to discuss with my dad since he is stationed right where my dad used to live, by the University of Chicago, where they split the first atom. My father was around then, playing around there, and always said there was just one old guy guarding it because nobody knew anything was going on.

“Yep,” Swing said. “That is what I tell ’em. That’s why the rats are so huge in here!”

I talked to Swing about what we were doing, in bringing Bobby home. He understood. He actually was among the guys first sent out to look for the body of Matt Maupin, the army private first captured and executed by Iraqi insurgents in 2004.

It sounded like something out of “Saving Private Ryan.” They didn’t quite know what to do, and it was a bit terrifying to risk their lives just to bring someone’s body back.

“But,” he said, “I thought, I would want them to find me. I would want them to bring me home. I mean, not a big deal, but if you aren’t doing anything better, I would like to come home.”

Maupin’s body was found in 2008. Swing might have been telling me he was one of those who found Maupin, but I didn’t know enough to ask.

The rain held off for Bobby’s funeral in Greenwood Cemetery in Rockford. CAO Lt. Col. Vince Barker wanted to invite his own family to the funeral, with our permission. He had spent so much time with my Aunt Joyce, even getting teased for being a Packers fan, since we are all Bears fans. He stood back and respectfully watched.

Lt. Col. Barker doesn’t do this all the time. In fact, he had never done anything like this before. He told me, “When we are notified that remains are coming home, the local reserve unit is tasked to assign a CAO to help the family, and because Bishop was an officer, it had to be a captain or above.

“I was one of the guys they called, and I said ‘Absolutely, I will do it,’ and I am glad I did. The whole circumstance, the whole story behind this is really unique and I am honored to be part of it.”

The Army Chaplain Gleason, who conducted the funeral, did so by request.

“I thought about what it would be like for a family, after 66 years – some closure is going to come,” Chaplain Gleason told me. “I remember one of my conversations with Joyce when she told me that she could remember going to bed as a girl, hoping and dreaming that maybe he would show up, from a concentration camp or some other means, and to think about that all those years and finally say ‘Okay, it’s probably over.’ And then to be able to bring back some type of remains.”

He wanted to be there.

THE DAY NO ONE IMAGINED

My father stood during the funeral. He was an 11-year-old boy when he waved goodbye to his Uncle Bobby on a cold street in Chicago. Now, he is 76 and stands with some difficulty on artificial knees.

The years between mark his service during the Korean War as a Naval Corpsman, his marriage and a long career with Alabama Power – the years between mark my entire life.

He said, “At the time we lost Bobby, we could not imagine this day. I, as a boy, could not imagine the world where it would be possible that my DNA would help us find him.

“Nor did I ever realize the Army would not rest until this day. I have always known Bobby was with God – and now he is also here with us.

“Thank you. Thank you for your service to our country, and thank you for bringing Bobby home.”

Among the mourners were World War II vets, standing at attention, and even more were moving- at least 30 Patriot Guard Riders. Many looked like Vietnam vets, but some were very young.

After the service, I walked the line and thanked them each individually. By the time I got to the last couple, I was crying, and so were they.

Later, I mentioned them to Sgt. Timothy Brown. He is in charge of casualty assistance in Illinois, and because there had been some confusion with my family getting to the airport, he personally drove my father and I back to Chicago.

He told me how great the Patriot Guard Riders are. He handled the Fort Hood funerals, and “for two soldiers,” we had at least 300 Patriot Riders a piece at the funerals.

HIS FINAL DUTY

Sgt. Brown is formal and dignified. But through some urging and journalistic prodding, I was able to discover that he has an incredible back story- one that makes his attention to dignity, respect and understanding of his duty inbred.

His grand-uncle fought with Patton. How few African Americans can say that lends spectacular insight into what kind of family this was even more, his grandfather played with Hank Aaron in the Negro leagues. He loved baseball but was a natural at football.

Playing only one year of high school football in Chicago, he was good enough for Gene Stallings to fly personally from Alabama to watch him play a high school game and recruit him. Unfortunately, he was injured and never played for Alabama. But he stayed with the team, and he and my father were able to have a very in-depth Alabama football discussion all the way to O’Hare.

I couldn’t help but think this all led him to a sensitivity to this particular duty. Obstacles and the trials of our families led us all to this place in time.

While we drove, he received another call concerning a World War II vet who had passed and excused himself to set up that funeral over the cell phone as he drove.

“A soldier’s funeral is his final duty to his country,” Brown told me. “So I will always be early, I will always be prepared. I want to make sure he or she is able to fulfill that duty.”