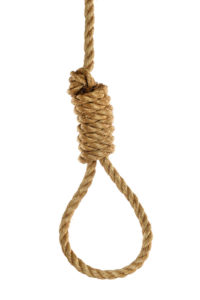

When I was 14 years old, a young man was hanged on the streets of a nearby town. His name was Michael Donald. He was only 19 years old. And he was black. It was March of 1981, and I can still remember hearing the news that a young black man had been found hanged on a Mobile street and my immediate reaction to that news: “It’s the 1980s. Not the 1950s. And they lynched him?!!” It was a reaction of disbelief, horror………….and instantaneous recognition of what had happened.

“They” were the racist rednecks. And this was racial violence. And it was still the 1980s and racist shit like this was supposed to have stopped decades ago. That was the kind of thing I was supposed to read about in history books, not hear about from the local news.

That instant recognition by a child of what had happened escaped the cognitive abilities of the Mobile, Alabama police. The Mobile police quickly, if not instantly, labeled it not as a racist lynching, but as a drug deal that went bad. (And it’s not as if drug dealers in Mobile were in the habit of leaving strange fruit hanging in the trees.) When I learned of the Mobile police’s inane assessment of the situation, it just confirmed yet again my opinion that adults were stupid, and that I was smarter than a lot of the adults because it was obvious to anyone with a halfway working brain what this had been. That, it turns out, a group from the Klan stood around that morning admiring the mutilated body from the comfort of a nearby front porch and that a cross was burned on the lawn of the Mobile County Courthouse in the wee hours of that morning were huge clues to the nature of what had happened. (Though I was unaware of any of that at the time.)

At another time the Mobile police’s dismissal of Donald’s lynching would have stood and nothing would have been done on the case. But this was the 1980s, not the 1950s. Michael Donald’s mother, Beulah Mae Donald, knew her son. Her marriage had ended shortly after Michael’s birth so on her own she had raised all seven of her children including Michael, the baby of the family, in a home that wasn’t filled with money, but was filled with love and God. She knew her son wasn’t involved in drugs. Mrs. Donald knew as instantly as I did what this was —– an old-fashioned Southern lynching. And Mrs. Donald wasn’t going to stand for some half-assed dismissal of her son’s murder and the smearing of her son’s good name. In June, her daughter and friends picketed the courthouse. In August, a protest with 8,000 people was organized and the Rev. Jesse Jackson contacted to lead it. Yet even under public pressure, the Mobile police failed in their investigation into the obvious. It took two FBI investigations to crack the case and for the ugly truth to emerge……..

Michael Donald was a picked at random because he was black and was alone. Walking home on the street at night he was a perfect target — vulnerable, male and black — for two Klan members, Henry Hays (26), and James Llewellyn “Tiger” Knowles (17), angry that a black defendant, Josephus Anderson, had not been convicted in the murder of a white police officer. Though the killing had been in Birmingham, Alabama, the Anderson trial was in Mobile and the mixed race jury had ended without a verdict that day. (Anderson was convicted in a subsequent trial.)

Henry Hays’ father, Bennie Jack Hays, a high-ranking Klan official in Alabama, blamed the blacks on the jury for the lack of a verdict and proclaimed “If a black man can get away with killing a white man, we ought to be able to get away with killing a black man.” And his son, Henry, decided to do something about it. So that night he and Knowles drove around looking for some black man to kill. Who it was didn’t matter. They found Michael Donald. They then abducted him at gunpoint, beat him, strangled him with a rope, slit his throat and hanged him from a tree on the same street where Henry Hays’ father lived.

Henry Hays was convicted of capital murder in December 1983 by a jury of 11 whites and 1 black who recommended life in prison. But the judge — in an unprecedented decision — overruled the jury to impose the death penalty. (Hays was executed in 1997, the only Klan member ever executed in the 20th century for the killing of an African-American.) Mrs. Donald opposed the death sentence saying,”You can’t give life, so why take it?” James Knowles, who had testified against Hays, was convicted of violating Michael Donald’s civil rights and was sentenced to life in prison in April 1985.

In 1987, in the first time they spoke together, Knowles would ask Mrs. Donald for her forgiveness. Mrs. Donald told her son’s killer, “I do forgive you. From the day I found out who you all was, I asked God to take care of you all, and he has.”

But Mrs. Donald’s story didn’t end with the conviction of the two young men who killed her son. She may have forgiven them, but she hadn’t forgiven the organized, deep-seated racism which was behind them. So in 1984 the Southern Poverty Law Center filed a lawsuit on Mrs. Donald’s behalf against the United Klans of Alabama. Again, I can remember my reaction when I heard about it. I admired her. And I was worried about her. It might have been the 1980s and not the 1950s, but there was no lack of racists rednecks in Alabama as this event had shown. I hoped nothing bad would happen to her.

After my father died, my mother worked as a maid cleaning quarters at the local Air Force base. Since I had base privileges, I would often go after school to the building where she worked and got to know some of the other maids she worked with, most of whom were black. One day one of them pointed out a woman to me and told me she was the woman whose son was lynched and was suing the Klan. I looked at the woman with respect, but I didn’t say anything. I’m not sure I’d have said anything if I were as old as I am today. As a teen I was tongue-tied. I admired her deeply and considered her to be a genuine hero. As an adult…………as an adult, I don’t know what you say to someone you don’t even know when what you know about her is her son was wantonly and horrifically murdered for no good reason and she had the guts to take on the bastards responsible. (And I have to add that I don’t know if the woman who was pointed out to me really was Beulah Mae Donald; all I know is what I was told at the time.)

In 1987, Mrs. Donald won her lawsuit and a seven million dollar judgement. Realistically she was never going to collect that seven million dollars. But she did get the deed to the Klan headquarters in Tuscaloosa, Alabama and the Klan filed for bankruptcy. I laughed when I heard she now owned the Klan building and cheered when I heard the Klan had to file for bankruptcy. After that, Mrs. Donald wasn’t the mother of a murdered son to me. She was the woman who bankrupted the Klan in Alabama. She was the first person to ever get a financial judgement against the Klan for the violence they perpetrated. Sadly, Mrs. Donald died the following year.

Having grown up with the story of Michael Donald and his remarkable mother, Beulah Mae Donald, I’ve never understood just why it is that the story isn’t better known than it is. If it happened today it would be national news for a week. There would be demonstrations and protests scattered across the nation. I’ve never understood why this story hasn’t been made into a movie as the story is tailor made for it. (And portraying Beulah Mae Donald would be the role of a lifetime for some older African-American actress.)

I’ve often imagined the movie, the credits a sequence of old newspaper clippings about race murders in the South with the song “Strange Fruit” playing. The opening scene of Michael Donald’s body hanging from the tree. The Klan members standing around watching and gloating. Mrs. Donald’s dismissal by the Mobile police. Her refusal to accept it. The involvement of a national figure in Jesse Jackson. The pressure finally resulting in a real investigation by the FBI. Slowly learning the story of what really happened. The trial. And in a normal movie that would be the end. But here the story continues with Mrs. Donald’s decision to file a ground-breaking lawsuit determined to get a judgement against the people behind the murder. Her dramatic in-court forgiveness of her son’s killer. Her final victory in bankrupting the Klan in Alabama. In the closing scene there Mrs. Donald would sit in the first house she ever owned surrounded by her children and grandchildren. And the end credits an echo of the opening scene —- the street where Michael Donald was hanged being renamed Michael Donald Avenue.

Why the tale of one terrible night in Alabama and what Beulah Mae Donald did about it is not better known, I’ll never know. It’s a story that deserves to be told and to be remembered.Â

—

Margaret has a blog, maggieameanderings.com